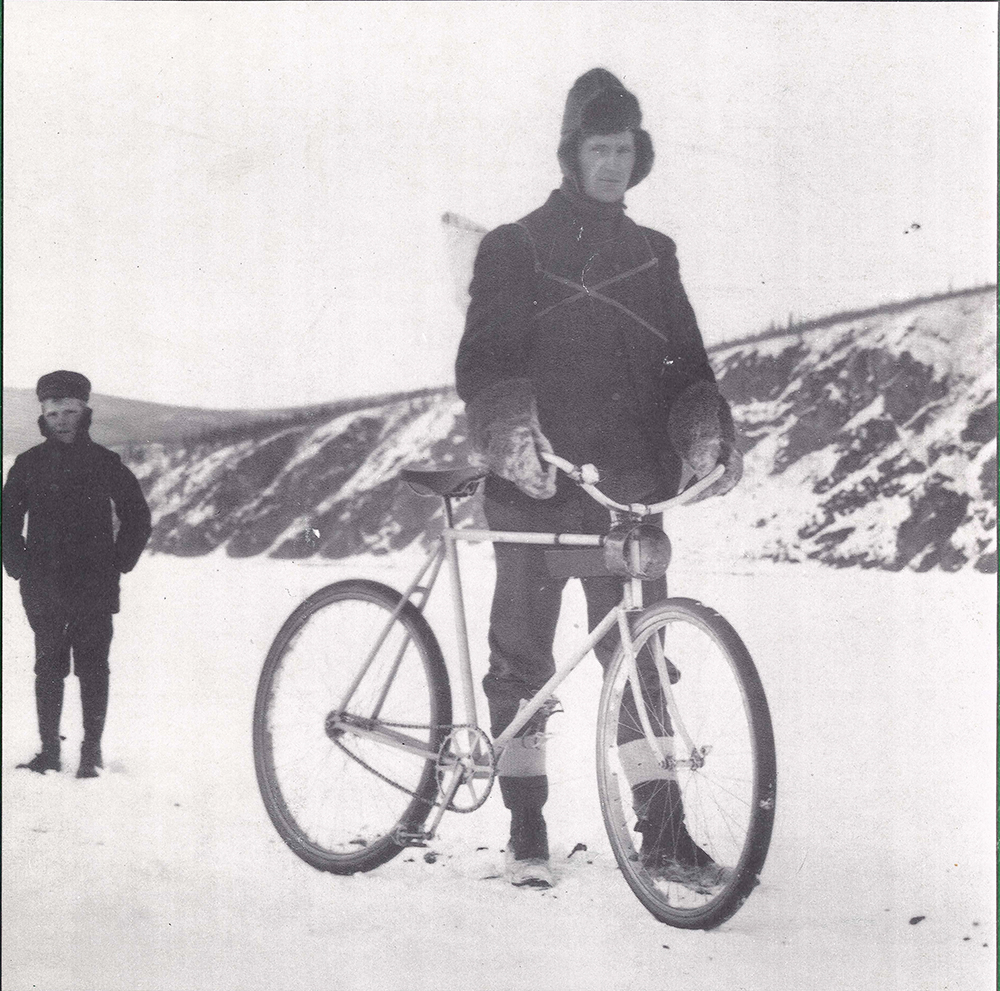

An unidentified wheelman who set the “overland bicycle record” from Whitehorse to Dawson City is pictured in the winter of 1903. He pedaled about 400 miles on the Dawson Trail in five days. As a comparison in modern winter racing, it took U.K. cyclist Alan Sheldon seven and a half days to ride 430 miles from Whitehorse to Dawson during the Yukon Arctic Ultra in 2009. Photo from “Wheels On Ice,” edited by Terrence Cole.

They were perhaps North America’s first endurance racers — the grizzled men and a few women who set out across wild expanses in a race to reach a land of uncertain but undeniably vast fortunes. The Gold Rush brought the notion of adventure racing to the forefront of American imaginations, because it was widely accepted that those who got there first got the gold — by any means possible. Klondike gold rushers sailed hundreds of miles on rough seas, hoisted a thousand pounds of gear over the steep and snowbound Chilkoot Pass, and emptied their life savings to buy dog teams and supplies to travel a thousand miles across the deep-frozen wilderness of Yukon and Alaska. Those who couldn’t afford dog teams used bicycles.

Modern winter cycling is a fast-growing trend, with enthusiasts touting the latest innovations that allow cyclists to ride bikes on snow. It’s a little-known fact that a hundred years before winter endurance races such as the Iditasport Extreme popularized snow biking, Klondike gold rushers were riding significantly more primitive bicycles across Alaska.

Wheelmen who embraced the bicycle craze of the 1890s believed that the bicycle was a logical vehicle to use in Alaska during the wintertime.

A Gold Rush-era company sold a special model called the “Klondike Bicycle.” A guidebook explained the bicycle was “in reality a four-wheeled vehicle and a bicycle combined. It is built very strongly and weighs about fifty pounds. The tires are of solid rubber, one and a half inches in diameter. The frame is ordinary diamond, or steel tubing, built however more for strength than appearance, and wound with rawhide, shrunk on, to enable the miners to handle it with comfort in low temperatures.” The bicycles had two fourteen-inch retractable wheels on which a miner could load a quarter ton of gear, and “drag it on four-wheels ten miles or so. Then the rider will fold up the side wheels, ride it back as a bicycle, and bring on the rest of his load.”

It’s unclear how many gold rushers actually used the combination cart-bike to travel a thousand miles. But for lighter-weight travelers, a bicycle was thought to have several advantages. Cyclists followed two-inch tracks left by the dogsleds, and they could generally travel faster than dog teams and horses under good conditions. The bicycles were less expensive to purchase and maintain than animals, and offered the user a greater margin of independence. After all, you don’t have to feed a bicycle. However, Far North cycling was wrought with hazards, as documented by the “wheelmen” of the Klondike. They suffered from snow-blindness and eyestrain, as well as numerous crashes from their efforts to stick to the narrow track. Bicycles also frequently broke down because of frozen bearings and stiff tires.

One of the cyclists who documented his journey was Max Hirschberg, a 19-year-old former Ohio resident and Yukon roadhouse owner who joined the stampede to Nome in 1900. The night before he planned to leave Dawson, he contracted blood poisoning while responding to a hotel fire. It was March before he recovered, too late to reach Nome by dog team ahead of the spring thaw. However, he reasoned, he was an experienced cyclist, and felt confident in his chances of reaching the goldfields before the Yukon River became unfit for travel.

“The day I left Dawson, March 2, 1900, was clear and crisp, 30° below zero,” he wrote in his journal. “I was dressed in a flannel shirt, heavy fleece-lined overalls, a heavy mackinaw coat, a drill parka, two pairs of heavy woolen socks and felt high-top shoes, a fur cap that I pulled down over my ears, a fur nosepiece, plus fur gauntlet gloves. On the handlebars of the bicycle I strapped a large fur robe. Fastened to the springs, back of the seat, was a canvas sack containing a heavy shirt, socks, underwear, a diary in waterproof covering, pencils and several blocks of sulfur matches. In my pockets I carried a penknife and a watch. My poke held gold dust worth $1,500 and my purse contained silver and gold coins. Next to my skin around my waist I carried a belt with $20 gold pieces that had been stitched into it by my aunt in Youngstown, Ohio, before I left to go to the Klondike.”

Outside of Dawson, the 1,500-foot-wide Yukon River had been through a rough freeze. Slabs of ice the size of cabins were littered along the banks, preventing access to the shore. Overflowing river water collected around the slabs, covered by weak layers of ice that broke when Hirschberg crossed them. “By the time I reached Forty Mile, my socks were wet and ice covered my felt shoes. It took me quite a while to orient myself to my two-inch trail and I had many spills on this early part of my journey.”

About 250 miles downriver, he reached the Yukon Flats, where the river was so wide and the landscape so flat that he could only see a few scatterings of trees on far-away banks. Otherwise, it was a moonscape. “The most dangerous and difficult parts of the flats were between Circle City and Fort Yukon,” he wrote. “Save for a portage land trail of 18 or 20 miles out of Circle City, the trail was on the river, which split into many channels without landmarks. The current was so swift that I encountered stretches of open water and blow holes. Snow storms completely obliterated the trail.”

In Tanana, near modern-day Fairbanks, Hirschberg encountered a forty-mile stretch of glare ice where the river had been wind-swept of snow. After numerous crashes, he broke a pedal, returned to town for a quick fix, and continued on to Nulato. The weather was warming, and numerous creeks were flowing with water. On the Shaktoolik River, he broke through the ice and nearly drowned. As he struggled in the water for nearly two hours, he lost his watch and his poke with $1,500 in gold dust, but managed to save his bicycle.

Hirschberg encountered open water on the Bering Sea, but started out across Norton Sound anyway. Just as he was nearing the opposite shore, the ice shifted, leaving an eight-foot lead of open water between him and land. “I took a chance and leaped to the shore,” he wrote, “where I picked up a piece of driftwood, jumped back on the ice floe and poled myself and my bicycle back to the shore, and went on my way.”

Just east of Nome, he skidded on glare ice and broke a chain. Unable to pedal any longer, Hirschberg found a stick, strung it through his large parka, and constructed a sail to catch the wind, which was blowing in the direction of Nome. “At times the wind was so strong that I was forced to drive into some soft snow to stop my wild flight,” he wrote. “Without my chain I could not control the speed of my bicycle. However, I finally arrived at Nome, May 19, 1900, without further incident. I had had my twentieth birthday on the trip.”

Hirschberg’s story would live on in the annals of “And You Thought You Were Tough,” and his survival instinct, unwillingness to quit, and innovation continue to inspire modern adventurers.

Great photos Jill – where did you get the first tow? U of A Fairbanks library?

Think of a thought.

(something your shooting for that’s worthy or to do some good)

Now just Imagine.

FEEL THE GLORY?

OF accomplishing the task.

IF YOU CAN FEEL IT.

“YOU CAN DO IT”

NEVER Stop Dreaming.

Always Keep Believing!

Never ‘EVER’ Give up!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In the course of a lifetime it’s amazing….

What we have control of each and every day…

To make our days better;

Being happy is a feeling.

Making it None-contingent on everything else….

Makes it one of the more delightful things to achieve every day.

CL

Wow. Great write-up. I had never heard about any of this before.

Jenn: First two are reproductions from “Wheels on Ice.” I’m not sure where the author received them, but it makes sense that they’re from the photo archives from University of Fairbanks. Second two are simply Google searches for Max Hirschberg.